Value chains: from linear to circular

Value chains today are viewed as interconnected and circular, not just linear: products are part of a larger system where materials are ideally reused and recycled, supporting a circular economy. This approach is key to reducing waste and keeping valuable materials in use. For example, the value chain of an electric vehicle (EV) battery includes mining raw materials like lithium and cobalt, manufacturing battery cells, assembling them into packs, and recycling or repurposing them at the end of their life.

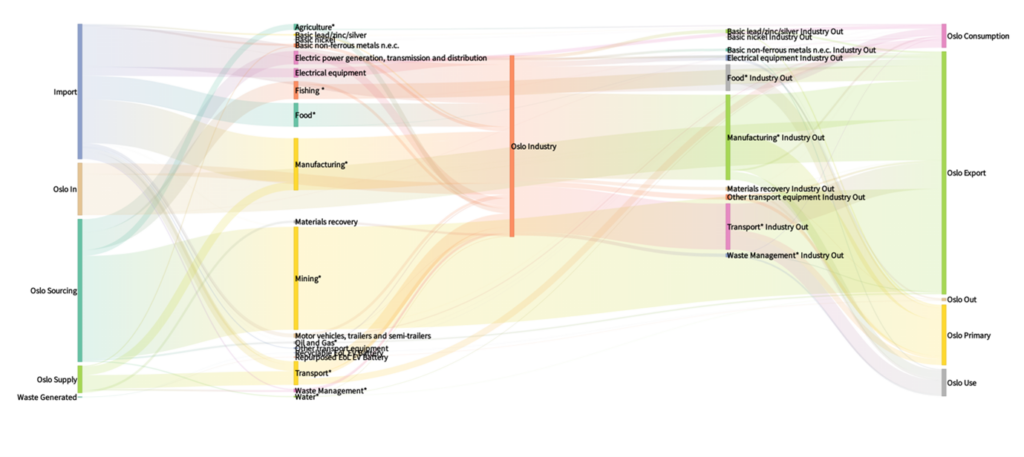

Value chain analysis usually includes outlining all activities in the value chain and looking at their costs and contributions to value. This helps businesses understand the specific actions involved in their operations, uncover chances for saving money, improving processes, and innovating. It can also help in making decisions about outsourcing, partnerships, and investing in technology and infrastructure.

Take a single product, like an apple. The apple has gone through transport, energy use, trade services, storage, packaging, and many other processes before reaching the consumer. Each of these processes has its own value chain, with its own goals that connect to the apple the consumer enjoys. Value chains were once seen as a straight line, from raw material production to final use and waste disposal. However, concerns about the environment and supply have made this view outdated. Reducing waste and ensuring that essential materials for new products stay in the economy, rather than being thrown away, are key goals that lead to the idea of circular economics.

Bioresource and Recycling Optimisation Model: BROMo

As part of the European Union funded project TREASoURcE, we have performed value chain analyses with a focus on circularity; for Norway, we have looked at electric vehicles’ (EV) batteries, their recycling, and reuse. The BROMo model was used to find ways for Norway to improve the recycling and reuse of these batteries. We have used input from project partners and literature to gather data for our model’s simulations.

A second life for Norwegian batteries

The study found that Norway’s recycling system for EV batteries is fairly developed but has areas of opportunity. BROMo indicated that there is a chance to recycle and reuse batteries, but the financial benefits are limited by issues like market saturation and geographical location. For instance, the model suggested that only batteries in Oslo and Fredrikstad are cost-effective to process due to the availability of recycling facilities and the high costs of transporting batteries from other areas.

The results showed that it is important to think about both the worth of reused batteries and the materials gained from recycling. The success of these processes relies on things like the value of the battery pack and how well recycling works. For example, reused batteries can be used in energy storage systems, helping to store extra renewable energy for later use. However, the worth of these reused batteries depends on how much energy they can still hold and the need for energy storage options.

We also found that recycling batteries to get valuable materials like lithium, cobalt, and nickel can also be cost-effective if the recovery rates are high and recycling costs are low. The study found that the profitability and retrieval of recycled materials can change a lot based on facility localisation, market conditions, and technology improvements, which we considered through a number of scenarios.

Value chain analysis models, such as BROMo, offer insights for optimizing material recycling in a circular economy. Norway’s EV battery recycling illustrates both opportunities and challenges. Understanding these factors helps companies and policymakers in developing strategies for resource management and waste reduction.

[1] This idea was introduced by Michael Porter in his 1985 book, “Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance”.

11.3.2025 | Gerardo A. Perez-Valdes (SINTEF Industry), gerardoa.perez-valdes@sintef.no